You might be familiar with “cobalt blue” pigment. You’ve seen it in ceramics and blue glass. That pigment has been known since antiquity and it became a fashionable choice for painters in the 19th century. Chemically it is called cobalt aluminate (CoAl2O4) and it is made by sintering oxides of both metals (cobalt and aluminum) at high temperatures.

Another cobalt compound is making the news, this one lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2). It is used in the cathodes of lithium-ion batteries. In fact cobalt compounds are used throughout the battery industry. All of your modern devices that need recharging are made with lithium-ion batteries. Or at least made from a similar technology, like nickel-cadmium (NiCad) or nickel metal hydride (NiMH), which also require cobalt.

The biggest demand for batteries is the EV industry. Electric vehicles are the future and cobalt is a key component. Here’s the problem: cobalt is hard to find. Big deposits exist in only a handful of places. One of those places is the Congo. The country is called the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) but there’s not much in the way of democracy there. 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from this African nation.

Three-fourths of the cobalt in the Congo is produced in industrial-scale mines. The rest is dug up by hand and by so-called “artisanal” methods. One can imagine the exploitative conditions the miners face in these primitive operations but apparently working for the corporations who run the big mines isn’t a whole lot better. The human rights record in the DRC is abysmal and the region is a source of continuing conflict among government troops and various rebel groups. Casualties among the Congolese and people in neighboring regions over the last two decades number in the millions.

Cobalt is a conflict commodity. A blood mineral. The perfectly reasonable goal of electrifying the world’s vehicle fleet comes with a steep cost in human life.

The other countries producing industrial cobalt are Russia, Australia, the Philippines, Cuba, Canada, China, Morocco, Papua New Guinea, and South Africa. There’s currently only one mine in the United States that produces cobalt. It’s in Idaho, in Lemhi County on the Montana border. Perhaps Americans ought to think about digging up their own stuff first before buying it from despots.

Cobalt is of crucial importance to animal life. Cobalamin, better known as vitamin B12, is necessary for metabolism and DNA synthesis as well as playing a key role in both the circulatory and nervous systems. Humans have to have it in their diet. Mostly we get it from meat, fish, and dairy food. Vegans have to pay attention to B12 uptake, and many use supplements like yeast extracts. Many common grain-based foods are enriched with B12.

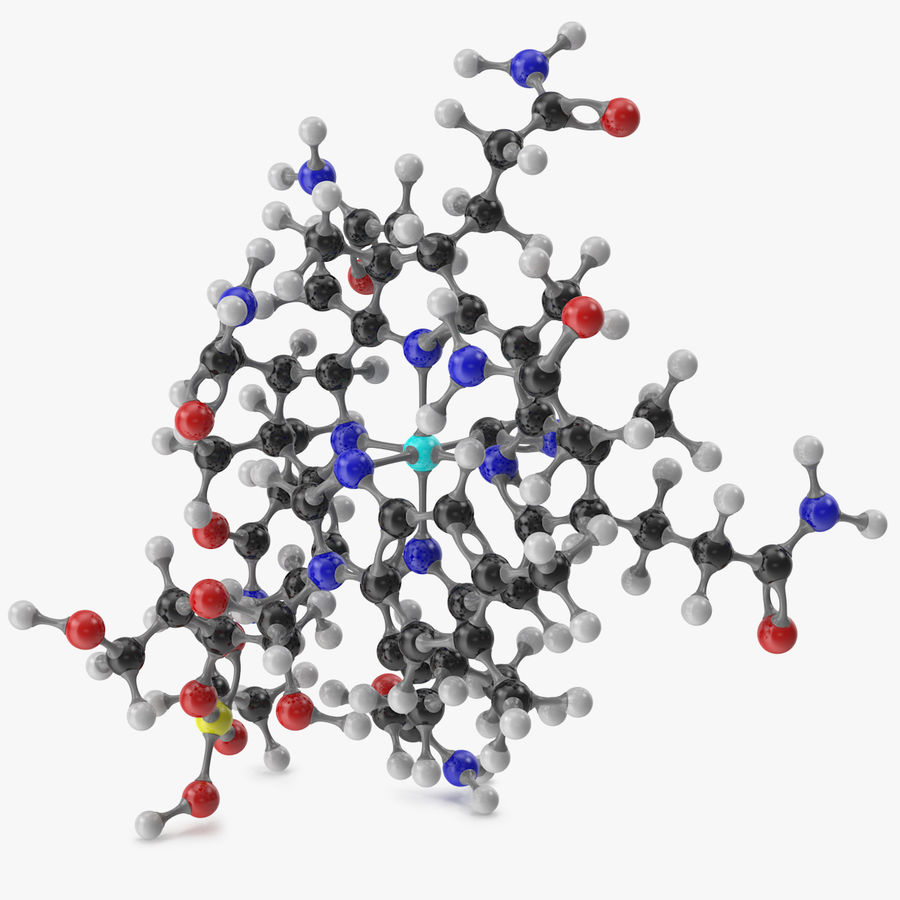

Cobalamin comes in more than one molecular form. Cyanocobalamin is the one most often manufactured—via microbial fermentation—as a food additive. Here’s a cool model of the molecule that you can buy for only $59! The cobalt atom is the blue-green (“cyan”) colored ball in the middle:

Like its neighbor iron (#26) this metal atom is a critical piece in the complex building blocks of life. Cobalt’s role in evolution is a very ancient one. Today we modern humans are suddenly in need of cobalt compounds on a very large scale. Let’s hope we can find a way to do it right.