Carbon is fundamental. There’s no life (as we know it) without carbon’s ability to make covalent bonds with other atoms like hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S). Take a look at the chemical formulae for the twenty essential amino acids that humans require and you’ll see a lot of C, H, O, with some N and an occasional S. Take a look at DNA and you’ll get plenty of P.

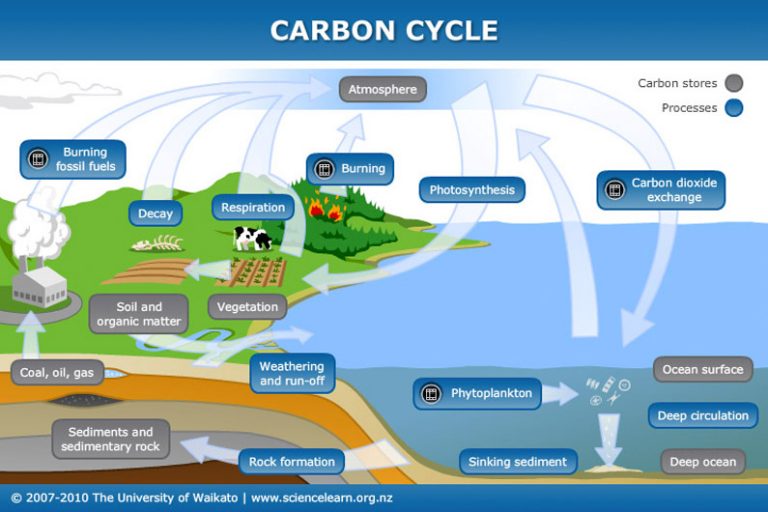

In college there are chemistry courses devoted entirely to carbon. They are called “organic” chemistry! That’s because all organic (that is, living or once-living) materials contain carbon. The classes have little to do with “organic” food and whatnot. Carbon makes such a byzantine variety of chemical combinations that an entire corpus of systematic nomenclature is devoted to these things. You don’t just learn about biological applications in organic chemistry, you learn about petroleum and its derivatives (plastics) as well. Fossil fuels are just that—fossils of once-living creatures. Oil is a mostly marine phenomenon, the source animals are plankton and algae, not Chevron’s dinosaurs. The gasoline we burn is from quite ancient places. The carbon atoms we liberate could have been there for 100 million years or more.

There is really only one thing to know about carbon, and that’s the carbon cycle. The earth is a vast repository of fossil carbon and we release lots of that fossil carbon because we are an industrial society. This of course has consequences. But carbon and its compounds like carbon dioxide cycle through every aspect of our existence even if we be Stone Age farmers. Carbon is life.

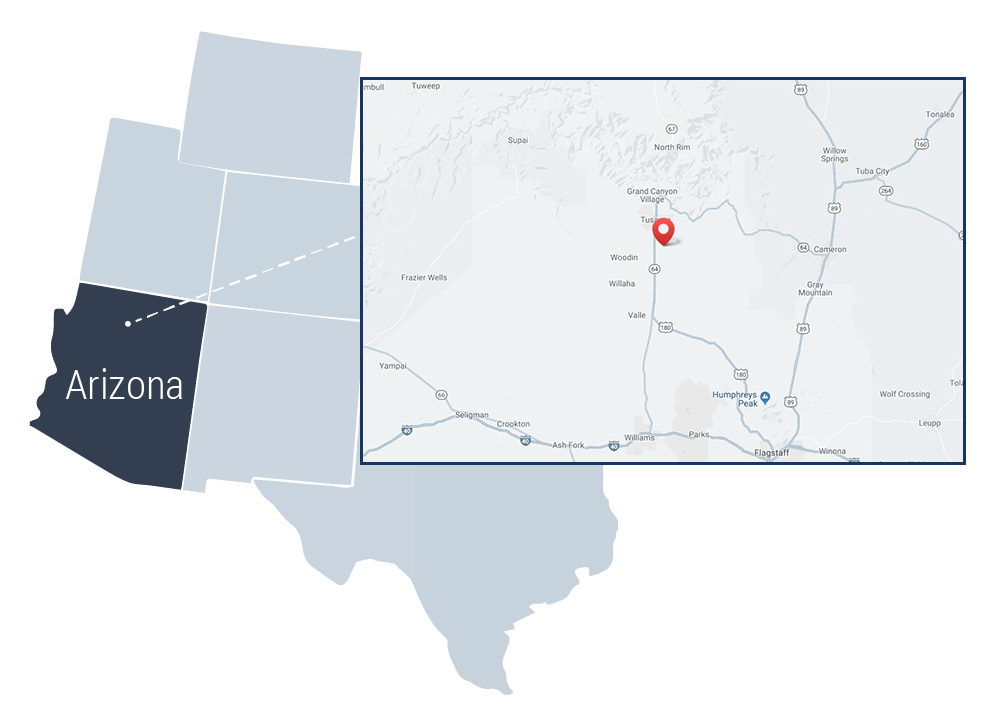

If you find something ancient, beautiful, and valuable on your land, what do you do? Do you extract it and turn it into dollars? Do you husband it for the future? Do you try to find a balance? That is, do you use the resource wisely? Do you think about externalities like clean air and water, quality of life, natural beauty, etc.? Is “value” in a capitalist economy only in terms of money?

I hope not.